Chapter 9

Events also continued away from the SIU campus. High schools, the “minor leagues” of SIU were very much affected by national events. Many high schools in 1970 experienced some type of demonstration, protest movement, walkout, or other response to the events of May. Just as at universities, many high school students tended to reject traditions and emphasize political issues. Students became more aware of the draft. Just as at universities, some of this heightened awareness was channeled in part to interest in broadcasting.

A few high schools actually had their own radio stations. At these stations, students had identified their interest in broadcasting and gained experience and skills. Many looked for a college that would further this. These high school stations were WIDB’s “minor leagues.”

Examples of Chicago area high school stations “feeding” WIDB were WLTL (Lyons Township), WNTH (New Trier West), and WMTH (Maine Township). Some high schools had aspirations of open air while running closed circuit, such as WEVN (Evanston). These would spit out fully activated radio people, often frustrated by the limitations of the high school station operation.

Picture the confluence. Age 18. Main interest: Radio & broadcasting. Have 1-3 years experience. Moving away from parental and high school authority towards all of Carbondale’s “stimulation.” Then, follow this up with contact with WIDB. For some it was a dream come true. The best part was that it was instant gratification–it was all set up, fully operational! There was no waiting list, no prerequisites, no departmental approval, and no entrance fee!

By Fall, 1970 the enthusiasm of the entering members could now be devoted directly and immediately to broadcasting, instead of construction, wiring, and administrative work.

Fall, 1970 began with fall quarter (remember, SIU was on quarters, not semesters. This was the last week in September, when WIDB resumed programming. WIDB had only broadcast less than 30 days in the spring before the riots closed the campus. Even though almost five months had passed, word had gotten around about WIDB, and many significant new members appeared.

Sam Glick had been Station Manager at WNTH. Dave Silver had been Chief Engineer at WEVN. Alan J. Friedman had been sports director there. Jim Rohr had worked at stations in Aurora. Mike Murphy and David R. Eads had worked at WLTL. Dave Schubert and Ron Kritzman had worked at WMTH. All of them, and many more, showed up at Wright I basement in late September, 1970.

“I found out about WIDB from an R-T Professor,” remembers Dave Silver. “He told the class that WIDB had nothing to do with “real broadcasting,” and we should all work at WSIU. I figured that I better check out WIDB. I also knew about WIDB partly because I lived in 217 Wright I.”

Jim Rohr was one of the few whose first encounter with WIDB was on the radio dial. “My parents had just dropped me off at Schneider to begin my first quarter at SIU. I got my stuff upstairs to the 13th floor, and the first thing I did was set up my stereo (which was an Allied phono/radio/speaker combo). I tuned the AM dial to find something appropriate for unpacking, and there weren’t many choices. But the strongest station was at 600 AM, and it had this peculiar hum that I had never heard on a radio station before.”

As Jim listened, he became more intrigued. “I heard hit music, jingles, and professional-sounding banter. I thought it was a tight-sounding, local station. As I listened further, the station’s location was recited as the Wright I basement. I had no idea where that was until I checked my campus map. When I found it, I made a beeline for the place. I left all of my stuff in boxes in my dorm room.”

While only 18 and a freshman, Jim had already worked at two commercial radio stations and one TV station. He was used to being on mike, doing news, and jocking. He thought WIDB was a local commercial station.

“I knew the station was on campus, but the idea of a student station never occurred to me. I figured that it was just a regular station that somehow was housed in Wright.”

So, within an hour after being dropped off by his parents, James Patrick Rohr walked through the door at WIDB. Twenty minutes later, he was on the air.

“The first guy I saw at the station was Woody Mosgers. He was the news director. Jim Hoffman (Jim Lewis on the air) was jocking. Woody and I talked radio, and I recited my experience. Woody said I would have an ‘on-air audition.’ No one else was there to do news, because it was the first few days of the quarter. News was up in ten minutes, and the UPI (news wire Teletype) machine was working, so there began ‘Rip’n’Read Rohr.’”

Jim ended up with a Saturday morning news shift. He recalls, after seeing WIDB for the first time, that it impressed him as an exciting, homemade vehicle towards adulthood. “It looked like a clubhouse for college kids and the students put it together themselves. There were record album posters, group photo posters, and a bulletin board with personal messages among staff members. It was only students, doing their own thing, just like being adults. I immediately felt at home there.”

Michael K. Murphy, then 18, was a two-year veteran DJ of the “WLTLivated Eleven” show on Lyons Township High School’s WLTL. But he never knew about WIDB until he encountered a Saturday morning charity basketball game (the WIDB DJs versus somebody) at the women’s gym. He met Jim Rohr and Robbie Davis and they encouraged Murf to check out the station.

“I had seen WGN, WMAQ, and WLS, and all of their equipment seemed old, large and clumsy,” said Murf. “At WLTL, we had hand-me-down ham radio stuff. By comparison, WIDB seemed big, clean and modern, especially the equipment. The people were energetic, enthusiastic, and optimistic. I knew I was going to enjoy working there.” Murf initially took a Saturday 9:45 pm 15-minute sports shift.

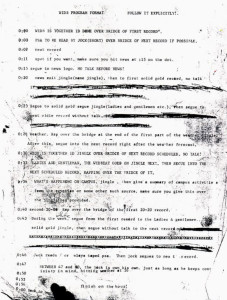

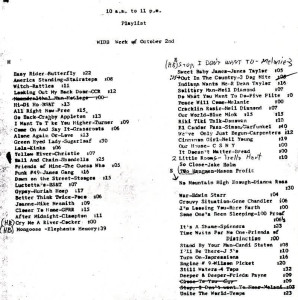

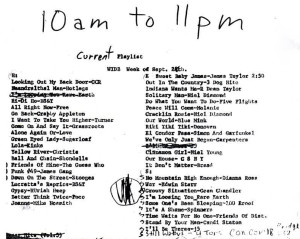

The broadcast year opened with Howie Karlin as PD, Tom Scheithe as Operations Director, and Jim Hoffman as Music Director. The station programmed from 7am- 1am everyday, until 4am on Friday and Saturday nights. From 10am-11pm, the crew was a DJ, newsman, and engineer. The jock chose records from a short list of single hits in categories. The Music Director created the list each week. Some weeks, only two or three selections changed.

The records were played each hour in accordance with a “pie clock” format (so named because it was displayed in a circular diagram cut into sections; like an analog clock, the category of record played and/or the jingle or news or weather presented depended on where the minute hand of the clock was) so that news was at :45, weather at :15, ID at :00 and :30.

This style of programming moved rather quickly. Most records were less than three minutes long. Often, breaks between records involved the jock talking on mike, a short promo, spot or two (on cart), a jingle (on cart), and then another record, which the jock would possibly talk over for a few seconds. As soon as he finished, it was time to select (and cue) the next record, decide what would be included in the break (jingle? ID? news? weather?) and set it up. When that was finished (if you were lucky), you might have up to a full minute before the current record ended. You could use that minute to answer the phone, update the logs, check the UPI machine, clear your throat, get a drink, and go to the bathroom.

This happened twelve to eighteen times an hour, 16 hours every day. It is easy to see why most jocks did not “combo.” This means they had someone else, an engineer, run the board for them. There was a separate control room, where the board, records, turntables, and cart machines were, and a separate “jock studio” where the jock sat.

The jock ran the program. He was in charge of selecting records (within the format). He cued the engineer for jingles, records, and promos. He signed the log. He was responsible for news if no one else showed. The jock turned on his own mike by a switch in the jock studio. He usually answered the request line. Often, he had to answer the other lines too.

The engineer ran the board. He set up the breaks and executed them. The best engineers anticipated what the jocks wanted. The best engineers were “tight.” Things flowed together smoothly, with no gaps, no beats missed, no “dead air,” and consistent levels.

The best engineer made almost any jock sound good. Although Sam Glick recalls that “There were only 2 cart machines and 2 turntables to do all this with.

Jocks could concentrate on programming (and schmoozing callers; marketing!) without being distracted with mechanics. Engineers could participate and contribute without needing extroverted voice skills.

Many became interested in production, or became jocks themselves. Almost all jocks eventually learned to run their own board, mainly because in most markets, stations required this. In the biggest markets such as Chicago, LA, and New York, however, jocks had separate engineers (often due in part to union contracts) and WIDB jocks wanted to “be like the big guys.”

From 11pm-1am, except Mondays, was “Underground.” It was free form. There was no format, no playlist, no jingles, no news. Usually, album selections were featured. Jocks were much more low-key. Programs styled like underground, were the forerunner of the “Album Oriented Rock” (AOR) style, which emerged two or three years later on the then-fledgling FM band.

In 1970, Underground and “Top 40,” (WIDB’s daytime format) represented the two major popular radio formats aimed at college-age people. Some at WIDB thought that WIDB should choose one over the other. But Howie, Jerry and others believed that, since WIDB was for ALL students, accommodating both formats made the station stronger, not weaker.

So in September, 1970, Howie and Tom had to come up with a schedule that filled five shifts (engineer & jock) plus underground, each day. That’s 35 shifts per week, plus six underground shifts (they had engineers too). So there were 82 person/shifts averaging three hours each week.

How did Tom and Howie fill these shifts before the university opened? All we know is that when Jim Rohr checked into Schneider, turned on his stereo and scanned the AM dial, there was WIDB, sounding attractive and even compelling to young James.

Meanwhile, it was Jim Hoffman’s job, as Music Director, to prepare the playlist. Still in existence are the first two playlists from Fall ’70.

The goal of the staff was to establish IDB as an integral part of campus life from the beginning of Fall Quarter. How well did they execute? Well, Jim Rohr found the station immediately on check in. A few weeks later, on October 21, 1970, a survey was performed: 5% of all dorm rooms were called between 3-4pm. WIDB had a 26.75 rating and a 75 share! At this point, WIDB had been on for only 30 days that quarter, and less than 30 days the previous spring.

WIDB staffers Woody Mosgers, Eric J. Toll, David R. Eads, Steve Berger, Mike Murphy and Roger Davis had compiled the survey. The survey also showed that almost 65% of the students interviewed said they “tuned to WIDB for campus and local news.” (In second place was “no station” at 15%, followed by WSIU at 6%). It came as somewhat of a surprise that WIDB was so respected as a news authority. But, not as surprising was the 26 rating and 65 share. WIDB staffers were hearing WIDB behind doors of rooms they walked past in the dorm corridors. When WIDB was mentioned in class or campus conversation, a portion of (but not all) students had heard of it. WIDB had accomplished its goals. It was established as an integral part of student life. People were listening, and they liked what they heard.

New members were attracted to the station. WIDB was meeting students’ needs in ways never done before at SIU. Students were depending more on WIDB than staffers realized.

A few weeks after the survey, in early November, the rising news department finished its in-depth documentary about the riots the previous spring. The one hour program “Seven Days in May–1970″ aired Sunday, November 8, 1970 at 10pm. Narrated by Jim Rohr, the program reviewed the sequence of events and the buildup to confrontation. Recorded actualities, featuring chanting crowds, tear gas grenades and sounds of violence prompted some listeners to respond as if the riots had resumed.

Although seven disclaimers were broadcast–that these were RECORDINGS of past riots, NOT live–they were not completely effective. Just as the 1938 “War of the Worlds” broadcast prompted panic despite disclaimers, some Thompson Point residents, in Baldwin, freaked out. ( Document #4–SI Article) One woman called her parents and told them to come and get her. The RC (Resident Counselor–one per dorm) claimed several students frantically sought shelter from tear gas. The RC, Joe Robinette, (apparently hired for his ability and training to handle such crises) determined that the problem was disturbing material that was being broadcast on WIDB. To solve the problem, Robinette ripped out the antenna cable from the WIDB transmitter!

Naturally, fallout ensued. Jerry Chabrian was outraged. No RC (or any other university official or person) was going to disable and/or damage a WIDB transmitter because they disliked the programming! It was more outrageous because it was informational programming, and controversial as well. Robinette was forced to explain, there was a flurry of letters via campus mail, and nothing ended up happening.

But two significant points had been made. One, the station would fiercely defend its right to broadcast free from censorship, and two, that WIDB’s power and influence over SIU students was far greater than most had expected. At this juncture, WIDB had broadcast less than one full quarter.

WIDB was flexing its interests in other ways that were threatening to the administration. Charlie Muren had a connection with booking agents for rock bands. The Rolling Stones were going on tour. They had an open date near C’dale. Charlie made a few calls. It was possible! WIDB could sponsor the Rolling Stones in C’dale. The only problem was the venue.

The SIU Arena was run by Dean Justice. He said that the university policy prohibited student-sponsored shows. He could not produce such a policy. Student Government weighed in. The policy did not exist. Justice said no shows could be booked without his approval. He would not approve student-sponsored shows. Students were too irresponsible.

WIDB and Student Government tried to appeal to selected administrators, but no one wanted to take on Dean Justice. Only the president or chancellor could overrule him, and even they were shy.

Through the years that the Arena existed, students had little voice in programming. Administrators would determine student programming needs. The ongoing administrative attitude seemed to be that student input was unnecessary and inefficient. They did not understand that music was a business. Dollars had to be watched. Because there was so much money flowing, administrators had to control that process. There was hardly enough money for administrators to control. There was little money for student activities. That was just for students.

By proposing that the station, not the university administrators, sponsor a show at the Arena, WIDB was threatening the existing system of money flowage. For that matter, just about any assertive behavior by professors or students was perceived as a threat to the existing system. Students attended SIU with the general goal of moving towards adulthood. Asserting one’s needs is part of that process. Doing so at SIU tended to make one the enemy of almost all administrators. Thus, SIU’s purpose: to encourage adult behavior was consciously disregarded by SIU administrators. Instead, adult behavior was punished. As students became more assertive, administrators acted more and more immaturely (attacking students, penalizing their grades, withholding funds from student activities, subjecting students to death and injuries, expelling and prosecuting students for “disorderly conduct” because gangs of police “legally” bashed in students’ heads, etc.)

The reason why a student radio station took so long to establish was that it represented students asserting their right to decide for themselves. Moreover, as an information conduit, WIDB was regularly communicating examples of student assertiveness. When students rioted, WIDB was there. When Student Government took a stand, WIDB reported it. When the Overpass opened on October, 1970, WIDB was there to point out that completion was delayed for three years by the administration because money could not be found to protect students from death and injury; it was just not important enough. Almost two-thirds of dorm residents relied on WIDB for campus news. Even a such a dysfunctional administration must have realized what a threat WIDB represented. Especially when you consider that instead of waiting a day to read news that was some felt was filtered thru faculty and administration, WIDB’s reporting was always live, immediate and most importantly, unedited.

Charlie’s idea to sponsor an arena show seemed so simple and direct, and the response was so obtuse, nonsensical, and frustrating. There was speculation of corrupt practices, but no one dared to imagine the full scope of the problem at that time. It was just the beginning of a long educational process.

Meanwhile, word had traveled around the state about WIDB. A group of high school seniors visited the station in mid-November. They were from Evanston, and WIDB was already a factor for them in choosing a college! Nine months before, WIDB had no space and did not exist. By mid-November, 1970 at least some high school students were visiting SIU to make a beeline for WIDB. “The first thing I looked for was the adults, the bosses, the professors, the “supervisors,” said Gary Goldblatt, then 16, one of the visitors. “Then I realized that there were no “university officials” looking over the shoulders of the staff. The students were the bosses.”

Gary was impressed with the professional demeanor and discipline. He observed Scott Barry (Mark Ferry) jocking and Allan J. Friedman doing news. “Each of them prepared themselves before opening the mike. There was a format to follow, and they respected it. After every break, there were comments and criticism. They were serious about broadcasting at WIDB. It made me wonder if I could measure up to that standard.”

At any student station, turnover is high because people graduate or otherwise move on. There is always the challenge to constantly have an influx of qualified new members, as the senior members have one foot out the door. Although WIDB had been broadcasting only a few months by late fall quarter, 1970, General Manager Jerry Chabrian, Chief Engineer Dan Mordini, and Program Director Howie Karlin were having their last weeks at the station. By February, Charlie Muren was GM. By March, Bob Huntington was Chief Engineer. By April, Tom Scheithe was serving as Program Director.

In December 1970, Jerry was somewhat frustrated that the breathtaking momentum of the past year had slowed. But Jerry was a man of action. Irritated that the new state-of-the-art (circa 1970) Gates “President” on-air mixing console had not been installed, Jerry ripped out wires from the old Studioette console before break. (That Studioette console, half the size of the President model, then became the nucleus of the Production Room for years to come.)

Jerry’s actions forced the engineers to install the new board. They didn’t like it, but it was a benefit to the entire station and listeners. As usual, Jerry did what was necessary to get the job done.

The specter of the war and draft continued to cast its shadow over WIDB. Prior to Christmas break, Jeff Esposito (Jeffrey Thomas) received his draft notice. Instead of being at SIU and WIDB Winter Quarter, he would be attending boot camp in the Army. He was regarded as one of WIDB’s best jocks, and there was a sense of loss at the station. It also drove home the point that the war and draft continued to affect everyone.

As an outgrowth of Jeff’s upcoming last show the staff got motivated to pitch in for a special programming effort. During exams, just before sign-off for break, WIDB would pull an “all-nighter.” Students stayed up all night to study for exams, so WIDB would provide a program service all night long. The centerpiece of this would be Jeffery Thomas’ last show. Sam Glick jocked the early evening, before Jeffrey.

Jim Sheriffs came on later. Other staffers participated. Jim Rohr impersonated celebrity voices in mock interviews. Pat Becker impersonated an oversexed movie star. One of the higher moments occurred as Jim Rohr, impersonating Jimmy Stewart (the actor) claimed that he could receive WIDB on his clock radio “right next to KABC.”

Although broadcasting 24 hours in one day seems tame by today’s perspective, it was a big deal for the staff at that time. Many staffers gathered at the station for the broadcast. It was a party. This was the end of WIDB’s first full quarter of broadcasting, and most staffers were feeling a sense of accomplishment.

WIDB was now firmly and fully established. The next goals were to maintain, improve and expand. They proved to be infinitely more difficult, and just as exciting, as establishing WIDB.