Chapter 1

WIDB began not in 1970, but in the ’60s. At the time, being dissatisfied with existing radio choices and starting one’s own station was radical. Having an entirely student-administered, student-operated and student-staffed station was downright heretical in the ’60s as it was terribly threatening to then-existing power structures. Just having these ideas and seriously attempting to make them reality is quite amazing. Actually SUCCEEDING in the face of a horribly byzantine bureaucratic culture was nothing short of monumental.

This history is dedicated to Jerry Chabrian, a man who had a vision, saw the potential to activate multiple generations of students, and didn’t rest until he, along with others, made it happen. This history is also dedicated to all other “charter” and “pre-charter” members, without whose sacrifices and dedication WIDB would never have made it to sign-on. Lastly, this history is also dedicated to the special members over the years who have been obsessively fierce in their efforts to maintain and expand WIDB as a truly student-administered, student-staffed and student-operated service to the SIU/C’dale students and community.

The prospect of a radio station/organization such as WIDB represented a threat of change to almost all elements of the SIU landscape. Starting WIDB required either approval or cooperation from many interest groups in the university mosaic. This demanded very large amounts of skill, vision, energy, time, persistence, and consistency. A tremendous effort was required to make such a change in the culture. The general conditions, as will be described, are important, since these are what gave Jerry his opening.

If not for the draft, the riots, the major swelling of the adolescent population (and its resulting identity, power, and assertiveness), the breathtaking expansion of the university, the bumbling indifference to student needs by some faculty and administrators (and the sincere caring for students by others), the station might never have been born. As it was, opposing forces almost prevented WIDB from advertising, and has prevented WIDB from going open air in any (legal) form.

Some readers may have predisposed attitudes about certain historical events such as the Vietnam war, the draft and those who wished to avoid it, protests, agitation, violent protests, looting, police and soldiers tear gassing, beating, bayoneting and shooting unarmed protesters and curfew violators, etc. We do not now write this merely to disturb these attitudes. It can be painful to have formed an attitude only to be confronted with contrary evidence. Reports in this history of SIU events are based on documentary evidence and eyewitness accounts.

That said, if you too have eyewitness accounts and/or relevant documents of your own, please pass them along to us.

Otherwise this history will never be complete, and as well you’ll have to deal with your own predispositions.

This is a living, not dead, history. There is always new information to include. Please help us. Feel free to correct, amend, embellish. Tell us your stories about when you were in C’dale. Tell us how your experience in C’dale has impacted your life. Tell us about the unique characters you met and/or hung out with in C’dale. And, tell us about you and WIDB.

The entire nation and world endured dramatic change in the ’60s. SIU and C’dale experienced this as young adults and adolescents asserted themselves to demand more responsibility, power, and allocation of resources. The effort to create WIDB was part of this. WIDB was not about burning down buildings or exterminating the establishment. WIDB was about being independent, taking care of ourselves, finding our own identity, serving our brothers and sisters, and forming a positive and hopeful vision for the future. But WIDB, and those who made it happen, were not on an island. They were in the middle of a stormy environment fraught with continual change.

Just as adolescence is a time of great change for all of us, the 1960s was a time of great change for the United States. For the first time, the security and the credibility of even the President could not be taken for granted. Repeatedly, even routinely, the traditional ways of doing things were questioned and attacked.

By 1966, the proportion of the population under the age of 19 soared to the highest in US history. During the 50′s and 60′s, elementary and even high school students were subjected to repeated propaganda about the Bill of Rights, equal protection under the law, the Declaration of Independence, and the role of our courts in enforcing the laws. Some of us remember the televised images of the students who just wanted to attend a Little Rock high school only to find their way blocked by the Governor of Arkansas in the schoolhouse door, and the federal troops called in to clear the path. Or the picture of the civil rights marchers crossing the bridge in Selma, Alabama as the police and dogs attacked. And later, the films of battle in the faraway jungles of southeast Asia where the soldiers looked more and more like our classmates and friends every day.

From 1965-72, at least 50,000 men were drafted into the armed forces each year. Almost all of the draftees were sent to Vietnam. There, many soldiers in ground troops (“grunts”) suffered physical trauma, unspeakable emotional horrors, exposure to major drugs such as heroin (attractive in response to death and suffering), and generally used up their remaining adolescence and most of their adulthood. Sometimes, it was scary to see a veteran of Vietnam. Some found it hard to fit into anything. The government did little for them. The war was unpopular. After paying a large price, more than a few felt largely abandoned. For many, getting drafted and serving in Vietnam ruined their lives.

Suddenly, starting about 1965, there were some really good reasons for going to college. But many very draftable males could not afford college, and they came from families where no one had ever gone to college. Or, they were not “model students” in high school, and may have barely graduated. In short, they could never get into, let alone pay for, most colleges. That’s where Clyde Choate, Paul Powell, and Delyte W. Morris came in. Many of us know that Southern Illinois may still be Illinois, but it has more connection to “The South” than it does to Chicago. Through the 1960s, the South was known as “the Solid South” because politically, it was so fully and completely Democratic. This meant that from these areas, if one was elected to office as a Democrat, reelection (over and over) was a virtual certainty. In the state legislature, seniority (and being in the majority party) is power.

In the late ’50s and through the mid ’60s, Democrats were rising in power in Springfield. Clyde Choate, from Anna, had served in state House for years and became the majority leader. Almost no state money could be appropriated without his approval. Paul Powell (pronounced “Pawl Pal”) was essentially Secretary of State for life (he died in office in 1970, when investigators found his hundreds of shoeboxes packed with hundred dollar bills). Powell, from Vienna, had served in government for many years and had accumulated innumerable political favors. He also commanded a very large patronage army.

Illinois has always seen the push and pull between Chicago and “downstate” interests. Chicago seems to get the lion’s share by some accounts. Choate and Powell wanted to change that.

Meanwhile, things had been pretty sleepy in Southern Illinois since the tornado leveled Murphysboro in 1927. Other than the horrible coal miners’ strikes in the ’30s and the opening of the Crab Orchard Wildlife Refuge and lake in the ’40s, not much was going on.

In Carbondale, there was this little “Southern Illinois Normal College.” The “Normal” meant it was for teachers. The main purpose was to produce teachers for the area elementary and high schools. There were also agricultural and mining degrees offered. The school had existed since 1867, when its first permanent building, “Old Main,” was erected. Southern Illinois Normal College had never had more than 1-3 thousand students at any one time.

In 1948, Delyte W. Morris became “Dean” of the college. Later his title was changed to “Superintendent,” still later, “President.” By 1970, when he resigned under pressure, he had built an enormous empire that dwarfed anything southern Illinois had ever seen.

He had overseen the transformation of the little teachers’ college into Southern Illinois University, the largest employer in Southern Illinois. The student population had ballooned to almost TWENTY THOUSAND in 1968! Millions upon millions of state dollars poured into Carbondale as building after building (Thompson Point, Phase I, Morris Library, Ag, Pulliam, Woody Hall, University Center, Home Ec, Arena, Lawson, Life Science I, Comm, Triads, Neely, Thompson Point Phase II, Mae Smith & Schneider), shot towards the sky. Almost all of these were built after 1958, when Choate and Powell were at the peak of their power in Springfield.

Choate, Powell, and Morris had worked together to bring more money and power to Southern Illinois. They succeeded, but they got more than they bargained for.

In 1964, there were less than 4,000 students at SIU. The next year, there were almost 12,000. How and why were so many “students” drawn to Carbondale?

First, almost anybody who graduated high school could get in. You didn’t even have to take the ACT. Second, it was cheeeeep. Sixty bucks per quarter tuition, full time. That was equivalent to about twenty record albums at that time. No books to buy, because there was Textbook Rental (a service of the university), where you could rent all of your books for about 2-4 bucks per quarter. Third, it could be eeeeeeasy. There were hard courses if you looked for them, listened to any advisor, or you were unlucky, but most courses were “relaxed.” Fourth (and, for some, first) there was a fancy, expanding campus near state parks and a national forest.

Finally, 1965 was the first year of massive troop deployments in Vietnam, and the first year of major drafting to support this.

So if you were 18 in 1965, your choice was to either:

a. Come up with about $200, plus living expenses, go to “college” in C’dale,

have easy classes with plenty of time for partying; or

b. Get drafted and go to Vietnam.

Which one would you pick?

Neely Hall, with capacity for almost 1000 women, was ready for occupancy in Fall, 1965. The Triads (Allen, Boomer, & Wright), with capacity for almost 1,000 men, was also ready for occupancy in Fall, 1965. Mae Smith and Schneider (also 1,000 each) were ready one year later. Thus, about 4,000 new students moved in over a one-year period in this area alone.

Construction was also proceeding at Thompson Point, Southern Hills, and Evergreen Terrace. Eventually, all of these dorms would be able to hold over 7,000 students.

In the mid-’60s, the City of Carbondale had a population of about 12,000. Dial phones had just been introduced. There were certain establishments that had not been integrated. McDonald’s had just arrived, and was the only national chain represented. When the towers were under construction, locals would come to watch. Most had never seen a building of more than three or four stories. Carbondale was firmly entrenched as a backwater of Illinois, where not much had changed for decades. Suddenly, it was invaded by 12,000 rambunctious adolescents, most of them from Chicago! Carbondale would be forever changed.

Chapter 2

So you’re 18, and a new student in Carbondale in 1966. Like most, you want some music. What are the choices? There was a lot of great music being released at that time, but could you get it in C’dale?

First, almost no one had “stereos” as we know them today. There were no “affordable” component systems (separate amp/receiver, turntable, speakers, tape deck). There were no CD’s, not even cassettes. There were reel-to-reel tape recorders and decks, but they were expensive and out of reach for 80-90% of students. “8-tracks” were just starting. These were tape cartridges (similar to radio station carts) that had 1/4″ audio tape inside, and ran at 3 3/4 IPS. Each tape had four stereo channels of audio, and you could listen to one at a time. 8 track players were largely in cars (and this was the first time anyone could play recorded music in cars–stereo too) but there were some home 8-track units. Most 8-tracks were pre-recorded versions of albums, distributed by record companies. A few people had 8-track recorders, but these were rare, especially in 1966. In fact, 8 tracks were pretty rare (and expensive) until the late 60′s. Even by 1970, less than half of the students in C’dale had 8-tracks. 8-tracks were not high quality audio (but they were stereo, and better than AM radio), and the 8 track tapes and cartridges often jammed or otherwise self- destructed.

Most students in 1966 had some records (45′s and albums) and a “phonograph” to play them. A phonograph was a turntable that had its own amp & speakers (or speaker–if mono). Many phonographs had a “changer” feature; you could “stack” 45′s or lp’s on the spindle and the phonograph would play them one at a time. This was not good for the records, but this allowed for a longer period of music that you could select yourself, without having to get up and interrupt your time with your boyfriend or girlfriend.

There are few pursuits more central to adolescent life than the search—the quest. This transcends all eras; no matter what year, students in C’dale were asearching and ahoping. However, in 1966, the local authorities stood between the searcher and searchee. Under the legal doctrine of “loco parentis,” (crazy parents), the university enacted and tried to enforce these rules:

- No Co-Ed dorms

- No members of the opposite sex in dorm rooms ever

- Curfew: all women must be insid their dorms before 10pm weeknights, 11:30 weekends. Men were 11p and 12:30a.

- “Visitation” was allowed in lounge areas with a supervisor present, until curfew

- Violation led to suspension (house arrest) or expulsion from the university

Keep in mind that for men, “expulsion from the university” could mean a loss of the treasured 2-S student deferment from the draft. The university was pleased to speedily inform the Selective Service System (draft administrators) that a student was expelled. Induction notices would promptly follow. From rule violation to expulsion and induction into the military could be 30 days or less!

So the choice was between following the sex drive and being sent to Vietnam, or following the rules and getting really REALLY frustrated.

One way to try to cope with the frustration was to listen to music, yet the same old records got tired pretty fast. Many students were accustomed to a full dial of quality radio choices, but in Carbondale, there were few stations and almost none targeted a student demographic.

Scanning the radio dial in C’dale in 1966, one would find meager offerings. First of all, most people had AM only. Almost all students had an alarm clock device, and most of these were analog AM clock radios. Car radios were almost all AM, even cars with 8-tracks. There were no boom boxes, no walkmen (or walk women) just “transistor” radios, which were all AM.

So, what was on the dial? Well, the local station was WCIL. It was owned by the McRoy family, as it had been for years. At 1020 AM, WCIL broadcast daytime hours only. It featured shows like “The Trading Post,” where locals could trade a ringer washing machine for a meat grinder or a cesspool pump. Another top WCIL program was “Coffee with Larry,” hosted by Larry Doyle, the Sales Manager. WCIL played music, occasionally. One would hear the Ray Coniff singers, Tennessee Ernie Ford, Vaughn Monroe, Andy Williams, Doris Day, and maybe they would take a big risk and play some Johnny Mathis.

The major feature on WCIL, hour after hour, was commercials, and lots of them. Hearing more than 30 minutes per hour of commercials was not unusual. SIU sports, especially basketball, was also a big moneymaker for WCIL.

WCIL essentially had a local monopoly on commercial radio, and they milked it . By 1968 they also had an FM frequency at 101.5 mz. It was mono, and they used it to simulcast the AM. When the AM went off, so did the FM.

Also on the AM dial was WGGH, Marion. This was the local country station. You could also find WJPF, Herrin, WRAJ, Anna and WMCL, McCleansboro. Although some of the music was different than CIL, and there may have been local and network news distinctions, it was the same style of radio.

WSIU was available at 91.9 FM. Mono at the time, WSIU was the first local station that did not sound like WCIL. But there was no NPR at that time, and WSIU was on its own. Some R-T professors were pressed into service as radio hosts. One example was Dick Hildreth, who hosted a 1930′s music show for years. WSIU had a strong and wide-ranging signal, but most people did not have FM at this time.

This dearth of diversity encouraged listeners to reach out further. On the edge of the daytime range of AM were some St. Louis stations, and others. WKYX, Paducah, Kentucky, was available at 570 AM. KGMO, Cape Girardeau, Missouri, had an AM/FM. St. Louis offered KSD, 550 AM, KXOK, 630 AM, and KMOX at 1160 AM. KYX and KGMO eventually became top-40, but not until the early 70′s. KSD was “easy listening,” (called MOR then), with WCIL-type music but less commercials. KMOX was mostly news/talk, and they were the St. Louis Cardinals’ (baseball and football) flagship station.

KXOK was the only station playing close to a “top 40″ format. Yes, they did play the hits, but also lots of commercials with really bad production, and ancient, embarrassing jingles. Their jocks were very self-impressed and left much to be desired. Anyone who had grown up on Chicago radio could not take much of KXOK.

KXOK also had a poor signal into C’dale. In the daytime, it could be received in most cars and some dorm rooms, if you were high enough (i.e., if your room was on an upper floor–most students didn’t do that then) and if your window faced north or west. At night, the signal was weaker and almost impossible to receive.

At night, most local AM stations signed off or greatly reduced their power and this was the opportunity one did not get in Chicago– the chance to DX. This meant trying to receive faraway stations.

WLS, Chicago, was the main option. Clear channel, “The Big 89″ had a fairly dependable signal into C’dale starting about an hour after dark. The other 50,000 watt clear channel Chicago stations, WMAQ, WBBM, and WGN were also receivable in C’dale at night, but these stations did not play popular music. WLS and WCFL were competitors and both featured a “Top 40″ format. WCFL also had 50,000 watts, but at night, it was directional north and mostly east; not receivable in C’dale.

At that time, “Top 40″ included a great merging of diverse styles.

Recent top 10 hits included:

Eve Of Destruction – Sgt. Barry McGuire

Psychotic Reaction – Count V

Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag – James Brown

Mr. Tambourine Man – Byrds

Winchester Cathedral – New Vaudeville Band

We Ain’t Got Nothin’ Yet – Blues Magoos

Chain Of Fools – Aretha Franklin

Sunshine Superman – Donovan

The Crusher – Novas

Kicks – Paul Revere & The Raiders

King Of The Road – Roger Miller

Mother’s Little Helper – Rolling Stones

(I’m Not Your) Stepping Stone – Monkees

Scratch My Back – Slim Harpo

Groovy Kind Of Love – Wayne Fontana & The Mindbenders

Because there was such a mix, and the songs were short, this format attracted a large audience. Adolescents from the Chicago area had grown up on this type of radio, and it was a big letdown to arrive in C’dale and have no comparable radio service.

So, at night, large numbers of C’daleites tuned to WLS. And, that would be the end of this story. EXCEPT, WLS’s nighttime signal was not quite dependable enough to satisfy the needs of C’dale. It would drift, fade in and out, increase and decrease in volume. The audio would often distort. Sometimes, it did not come in at all. The general need remained unsatisfied.

So we have this open space, still in Illinois but essentially a foreign land, that suddenly experiences an enormous building boom and a huge influx of young adults–almost all from the Chicago area–who double the size of the town practically overnight. These “students” were attracted by loose admission and class requirements, new campus, cheap tuition, and a draft exemption. There was a lot of energy, leisure time, and a split feeling of invincibility and desperation.

18-20 year olds in 1966 were the beginning of the peak of the baby boomers. While growing up, they were repeatedly propagandized about the “Red Menace,” digging fallout shelters, and the glory of dying for our country in war. In 1966, the government propaganda tried to justify the vietnam war as a fight against the Red Menace, and that getting drafted for this was just as good as fighting Hitler. This was not well-received, especially in view of nightly news coverage of the war that contradicted the government. Many people, especially those of draft age, became uneasy, distrustful of authority, and angry.

Meanwhile, it had only been a few years (maybe since the mid-’50s), that an adolescent identity had been “allowed.” First, it was music, only for adolescents (rock & roll). Then it was movies (First, “Blackboard Jungle,” “Rebel without a Cause,” “The Girl Can’t Help It,” later, Beatles’ movies). Then, special clothes. There was special language (Groovy. Uptight. Freakout.) Cigarettes, cars, cosmetics. Hairstyles. Special activities (“Skateboarding” was originally called “sidewalk surfing”). There were special TV shows like “The Monkees,” Shindig, and Hullabaloo. We may take this for granted now, but, prior to the mid-’60s there was very little “generation identity.” But now, added to the general feeling of invincibility adolescents always seem to have, there was a pervasive feeling, for the first time, that this generation was a TEAM, they had some power, they had their own way of doing things and MAYBE they were strong enough to avoid being pushed around.

In 1966, SIU had enough students to qualify as a major state university. Yet, in some ways, the school was run as the small college it had been just a few years ago. Springtime meant panty raids. Panty raids involved a crowd of males gathering in front of a female dorm. The females were supposed to “satisfy” the frenzied males by tossing panties out the windows. At some point, the males would leave with their panties and go home. From today’s point of view, it all sounds pretty tame.

In 1966, spring came early to C’dale and the sap was rising as the panty raiders were out in force. Yet they were too impatient to wait for their panties, so a few enterprising males invaded the dorm to find the panties themselves. The dorm matrons were outraged and they complained to the security police and the administration. The offenders were expelled, with no right of appeal. Since they were male, this meant they would be drafted, and likely be sent to the jungles of vietnam, in a matter of weeks.

Students were outraged. How could their comrades be “sentenced” without a hearing, and with no right of appeal? This was not the American way as they had been taught for years! What about constitutional rights?

Here we had the age-old conflict between abstract principle and practical application. The idea of constitutional rights to due process and to petition for redress of grievances versus keeping order in the face of “doing things not normally done.” In today’s world, the reaction would probably be individual, and one extreme or the other. Either the offenders would be afraid of “getting in trouble” (i.e., interfering with their future job prospects), afraid of “rocking the boat” (being branded as different), or just feel powerless and they would do nothing. Or, they would get a lawyer and sue. Either way, an individual response. In the late 70′s or early 80′s, getting expelled from SIU for being overly zealous at a panty raid would likely be worn as a badge of honor. It would not be perceived as restricting anyone’s future

But in 1966, most students were not concerned about future earning power. They were concerned about their chances of surviving until next year. Getting drafted lowered those chances substantially. And expulsion meant getting drafted.

The effect of the expulsions cut across students as a group. Almost all male students were subject to the draft if expelled. Almost all male students felt that panty raids were reasonable, necessary and proper, and most certainly not an expellable offense. If they were going to be arbitrarily expelled and drafted, they had nothing to lose.

So the panty raids increased. The crowds got larger. The administration and police were scared. Martial law was declared. A curfew was imposed.

There were meetings among faculty, administration and student representatives. The faculty and administration agreed that the students needed to be taught a lesson. As it turned out, the students did teach themselves a lesson. But, it was the faculty and administrators that were taught the big lesson.

In defiance of the curfew, larger and larger crowds gathered in front of the female dorms, A “police force” approached. It was comprised of SIU Security, C’dale police, Carbondale Volunteer Firemen, and Jackson County Deputy Sheriffs. They decided to arrest as many curfew violators as they could. There were more than a hundred arrested, so there was no way to transport them to a lockup except on foot. So the cops tried to march the group down to the police station, then located on Washington Street south of Main.

Once they arrived, the police realized that the lockup only had room for maybe a dozen. So they told the group to wait on the street until the cops figured out what to do. The offenders then decided to leave. En masse, they proceeded to Freeman and Illinois (where Spud-Nuts was then, east of where Quatro’s is now). They started rocking cars. The cars were turned over. Some were throwing rocks and breaking windows. The cars were burning. The police were powerless to stop the students, and this was obvious to everyone.

At the police station, network news crews were present when the police told the student “offenders” to wait on the street while the police figured out what to do with them. One of those students was Roger Strauss, then 19, a student from Chicago. Roger was shown on camera when he was across the street from the police station. In the picture, Roger was giving the police “the finger.” The story made the network news, at a time when “campus riot” stories were still unusual.

Imagine never hearing of Carbondale, Illinois before, never hearing of Southern Illinois University before, and seeing, on the network news, a shot of a student giving the “universal salute” to the police AT THE POLICE STATION! Remember, this was still 1966, when protesting was still new and unusual. Imagine being in Los Angeles (where Roger’s aunt was) and seeing him on KNBC.

Carbondale? That’s the place where the students give the police the finger! This is the first image many people had of C’dale and SIU. (If this happened today, the cameraman and crew might well be arrested and charged with “inciting a riot” or at least “disorderly conduct,” and the university could claim that the shot was “staged” and that “nothing happened.” The university might complain that NBC was portraying the university in a “false light” and threaten to sue. Never mind that this was caused by the university’s manic response to a panty raid; sentencing the violators to potential death or dismemberment in Vietnam.)

The faculty and administration still insisted on teaching the students a lesson. Meanwhile, the news was getting around. Responding to nationwide publicity, members of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) visited C’dale, and conferred with local students at Spud-Nuts. The SDS members were interested in the national statement potential of events in C’dale. Up to that time, most protests were confined to the east (Columbia) and west (Berkeley) coasts. Carbondale was extremely middle-america, so if it could happen in C’dale, it could happen anywhere.

The protests escalated. Crowds continued to gather every night, in defiance of the curfew. Responding to this activity in 1966 was impossible for even a large police department such as Chicago’s. In C’dale no one had a clue what to do. All the offenders couldn’t even be arrested. Those that were could not be locked up; at the C’dale police lockup, there was room for maybe ten. At the Jackson County jail maybe 20 more. What about the other 2,000? There were at least 50 offenders for each officer. The police were scared. Martial law became a joke.

The administrators and faculty continued to insist that the students be taught a lesson. But how? Hire 1000 more police? Build a new prison? (This was eventually done, in Vienna, a few years later). Expel 2,000 students? Who would come to school there? The debate raged on among faculty, administration, and student representatives.

Rumors abounded among students: The protesters were burning down buildings. The police were murdering students. Students were burning police cars with police still in them. The campus was going to be turned into a concentration camp. The police were training vicious dogs to maim students. Anyone who went to class would be attacked. Police were working undercover, posing as students. The dorms were going to be tear gassed. The roads out of town were blockaded.

There was no medium to instantly communicate to students. Print was the only option, and it was cumbersome. It was slow, not pervasive, and ineffective in response to word-of-mouth rumors. The “word on the street” was considered by many to be the most reliable and credible information. And, once exciting events were happening, “word on the street” spread at lightning speed!

Slow to respond, the administration finally decided to create an “informational discussion” program on WSIU-FM. The program was designed to convey the impression that calm and serious discussions were happening among students, faculty, and administration. Since, at the time, probably less than 5% of students could listen to FM radio, let alone those who could find WSIU on the dial and were aware of the program, it had limited results.

Meanwhile, word-on-the-street was to gather at the president’s house. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, massed and began moving in that direction. By now, National Guard troops had been called in. The troops and police narrowed the crowd and a select group of students went to the president’s house.

President Delyte W. Morris met with the students, in the street. There were a total of 20 persons standing together. President Morris and three associates stepped towards the group of 5 students. He was cordial to the students. He said, “How can we get past this?”

The reply was, “Reinstate the students who were expelled for the panty raids and curfew violations.”

He said, “I can’t do that for the good of the university.”

The response: “Look down the street.”

Students were rocking an Army Jeep with a machine gun turrent. They were screaming, especially when it turned over. A police car was burning. Dozens of students were wearing “First Annual SIU Riots” T-shirts. The crowd chanted “The town’s going to fall,” over and over.

President Morris issued a memo reinstating the students. The students had learned a valuable lesson. But it took awhile for the administration and police to learn theirs.

Chapter 3

The SDS was encouraged by the response of the students in C’dale. By the next school year, (66-67) there was a local SDS chapter. Rumors abounded that the Weathermen were also involved. It would be too tangentially lengthy to detail the development of the SDS and its sub/splinter group, the Weathermen. It shall suffice to say that both groups advocated great change in our systems. Both groups felt that at least some existing institutions must be dismantled and/or destroyed before improvement could start. The Weathermen splintered because they were more impatient than the main SDS group. The Weathermen, at least at times, advocated change through violence.

So we have the “First Annual SIU Riots” in spring, ’66, and then, a few months later, the creation of a local SDS chapter with rumors of Weathermen. At the time, the administration’s largest fear was the presence of “outside agitators.” This meant people coming to C’dale from parts unknown for the purpose of facilitating unrest.

To some extent, this fear was well-founded. There were sources of support and consultation outside of C’dale that assisted in organizing demonstrations, orchestrating events that pressured the administration, and teaching techniques of negotiation. But this potential led nowhere unless there were large numbers of locals who were motivated, angry, and competent. The administration was convinced that, except for these “outside agitators,” SIU students would remain preoccupied with good times, cars, and panty raids. The truth was that students were concerned and angry, especially about the draft, war, and related issues. This created the “gun powder,” and all that remained was for someone to light the fuse.

Many students, perhaps most students, did not actively participate in violent acts against persons or property. The same can probably be said about police and soldiers. Yet there was a significant and ever-fluctuating minority on each side that continued to support a hard line. All of the “fuse-lighting” events made tempers rise. The aggression was hard to keep in check. Both sides knew violent acts by their own group alienated “middle america” persons. Some did not care about what “middle america” thought, and believed it was more important to “send a message” by engaging in violent acts.

During the years 1964-72, there were buildings burned and/or bombed on many campuses all across the nation. Many in C’dale felt “it could never happen here.” Yet, in the spring of 1968, a bomb was detonated in the AG building, which extensively damaged the auditorium and other areas. Luckily, the explosion occurred when the building was unoccupied; the potential number of injuries was unthinkable. This event significantly raised the stakes, and all participants became very edgy.

Events leading up to June of 1969 are largely unknown to this author. Perhaps some readers can supply some information to fill the gaps. What happened that month in C’dale was an event that is usually mentioned only in whispers, even 30 years later. Although it affected everyone in C’dale at that time and for years to come, it is not allowed to be mentioned in the SIU Museum. The investigation was never closed, and never resolved.

There was a large building in the middle of the old campus. It was basically among old Davis Gym, Shryock Auditorium and Altgeld Hall. It was the oldest standing building on campus, about one hundred years old. It was the main classroom building. The English Department, among others, had its offices there. The building had a large clock tower. Its image was featured on the seal of the university, on brochures, etc. It was the central point of the campus. It was called “Old Main.”

At that time, SIU was on quarters, not semesters. Spring quarter began the last week in March, and exams were the second week in June. The day before the English exams were scheduled, the word on the street went out: “Old Main is burning.” The building was not only on fire, but engulfed in flames. Although it had a brick exterior, the interior featured many flammable materials.

Crowds gathered to watch it burn. Firemen were largely helpless. No one was killed or injured (as far as this author knows), but the building burnt to the ground. News of this traveled nationwide.

Meanwhile, in the mid-60′s, a special person was coming of age in Chicago’s far northwest suburbs. His father had an electrical contractor business. While still in high school, he got a part-time job at a nearby suburban FM station. He was independent-minded, strong-willed and very determined, traits that would later become the indispensable contribution to the ultimate goal. He graduated high school in 1967, and decided to attend SIU in the fall. The SIU he discovered was very much in flux.

The campus and community had not yet adjusted to SIU’s manic growth spurt. Housing for students was still in short supply. Trailer courts, makeshift temporary dorm space (accommodating as much as 3 or more in a regular room), administration buildings and temporary “barracks” were pressed into service for housing. The campus’ state seemed to be continually “under construction.” Buildings were always being built, sometimes in twos and threes. Despite all the construction, sidewalks and walkways ended up last in priority, so there was nowhere to walk except on the grass. Yet since the grass was perpetually torn up because of the construction, everyone had to walk on the dirt. Add to this mix that it seemed to rain A LOT in C’dale, which turned the dirt turned to mud very quickly, significant portions of campus regularly became quagmires.

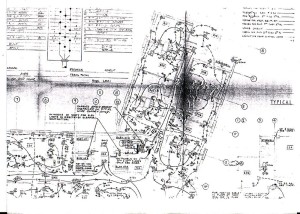

Sometimes, wooden “snow fences” were laid on the mud to assist in walking through the mess. This worked out all right for the first 1,000 or so persons; not as well for the next 5,000. The construction of Schneider, Neely, Mae Smith, Allen, Boomer and Wright dorms, along with Trueblood and Grinnell Halls, created a significant “East Campus.” SIU was now split, with the Illinois Central Railroad tracks and US Route 51 right in the middle. Thus, students living at or visiting the east campus had to cross the tracks and Route 51 every time they wanted to get to the main campus area, to go to class, just about any university office, the University Center, the Arena, or Morris Library.

Now, there are walkway/bikeways/overpasses over the tracks and Route 51 that people use. In 1967 these were not there. In 1965, the university had approved construction of the overpass, and construction began that year. But construction was suspended in 1967 because proceeding with construction exceeded original cost estimates. Years passed, and students continued to fall victim to pedestrian/auto, and pedestrian/train collisions. The university bureaucracy still would not proceed with construction. Only after another major accident resulting in a student’s death in December 1969, along with vehement student demands for completion of construction, did the university finally move ahead.

In 1967, there were three main areas to cross. One was at Grand, where there were sidewalks, railroad crossing gates, and a traffic light at Route 51 (Illinois Avenue). That was pretty safe. Another was just west of Grinnell (where the first overpass was finally finished in October, ’70). This was where the most traffic (and the most danger) occurred. The third spot was between Wright and the Physical Plant (where an overpass was built in the late ‘80s). This one featured a hilly area that led down to (and up from) the tracks. When the “hilly areas” were barren (which was most of the time) and it rained (often) the hills became mudslides. When one noticed another student with a “muddy backside” there was a grunt of empathy because almost everyone had, at least once, attempted this route only to take a slide in the mud. In fact, this last crossing became known as the “Ho Chi Minh Trail,” named after the route in Vietnam that the insurgents traveled, famous for its “monsoons” and mud.

So it was clear to all who came there that SIU was a “work in progress.” The campus was evolving, and the many new and ongoing projects were threatening to certain administration and faculty personnel. Those who were unsettled by the changes were concerned about keeping the traditional priorities in order. Yet, there was continuing debate over just what those priorities were.

For years, some schools had been run as if serving student needs were afterthoughts. There was a rationale that what was good for administrators (and some senior faculty) was good for students. Concurrently, established protocols and procedures of decision-making and grievances, in place for years (even decades), were stubbornly defended by administrators and faculty. The old methods certainly offered administrative convenience to those in power. It also kept the defenders in control of most spending and personnel power.

The massive expansion of SIU was made possible by the support of, and promises of benefit to, unions, local and other contractors and vendors, certain politicians, and local businesses. All of these groups stood to enjoy financial and/or political gain from the massive influx of government dollars into C’dale. It was these interests (and not those related to higher education and the students who sought it) that coalesced to make the state commit the dollars to SIU, and it was these same interests that were represented on the SIU Board of Trustees. That being said, those in power were aware that state dollars would cease if there were no students. But, in the ‘60’s, there seemed to be an endless supply of students.

Attracted by the new campus, cheap tuition, and (for some) draft exemption, new students kept coming to SIU. Many never graduated, but they paid their tuition, spent money with local merchants, and fulfilled their purpose. So, as long as the students kept coming and spending, priorities were “in order;” but only as long as the students “behaved themselves.”

“Behaving” meant two things: (1) Not committing any crimes or violating criminal-like university rules; and (2) Not interfering with the established protocols and procedures of the university. If a student ran afoul of (1), he or she was branded a “criminal” by the administration; if a student breached (2) he or she was labeled a “troublemaker.” Time after time, there were examples of the University making decisions based on what was perceived to be in the interests of the faculty, businessmen, politicians, administrators, and university protocol and procedures, with almost no consideration for what students needed.

One example was the expulsion of the panty raiders in 1966 and the stubborn insistence that students “must be taught a lesson.” But this last-placed student priority was blatantly obvious in proposals that were exclusively for student benefit, with almost no perceived benefit for the “in-power” groups.

The stubborn refusal to complete the overpass construction for over three years while student after student were mowed down by speeding cars and trains is a pretty good example. Where was the benefit to the administrators and faculty (who rarely walked to East Campus)? It was a “small” (read: “cheap”) project, and there were so many other projects that could put dollars into local contractors’ and union and union members’ pockets; how could this be a priority? It is inferred that only after the perception that defending and settling lawsuits became more costly than completing the project did construction finally move forward (after a teamsters’ strike, major riots, and intense student pressure).

Keep in mind that money was not a problem (the way it is today) at SIU. There was a mindset that the university was expanding, the state was committed to fund this, and the state had the money. The university’s budget increased dramatically each year, including a hefty construction/capital improvement component.

There were other sources of money besides the state. The university created certain “funds” that were earmarked for particular purposes. These were where the “fees” that students paid every quarter (in addition to tuition) were deposited. One example was the infamous “SWRF” fee. The “Student Welfare & Recreation Fund” became one of the more controversial fees. This is how it worked: each quarter, after one registered, a “fee statement” would be rendered. On it, your tuition was listed, along with a few bucks (5-15) for “SWRF.” Other fees (such as the Athletic Fee) were also listed. Even if tuition was paid, one was not registered unless all fees were also paid.

The ostensible purpose of the SWRF fee was to erect a building containing recreation facilities for students. However, this fee was collected from almost all students, quarter after quarter, semester after semester, year after year, through the 60′s and into the 70′s, with still no new student recreation facilities. Students complained for years that they were paying for nothing. The now-infamous SWRF fund accumulated millions of dollars. Finally, in the mid 70′s, after years of controversy and pressure on the SIU Board of Trustees, they authorized construction of the co-rec center with these funds. It was eventually completed in 1976.

Some argue that the administration and Board might never have authorized construction but for the years of riots and student pressure to use the funds and build a recreational facility. The Board and administration seemed to resent the student pressure, year after year, to abolish the required fee payments or build something that addressed students’ needs. In a final rebuke to those who had made the co-rec center possible, the Board of Trustees, upon administration recommendation, voted to bar admission to the co-rec center to former students who had paid the SWRF fees and pressured the Board to build the building!

So we have this result—alumni who paid their hard-earned student dollars for years (and got nothing but empty promises in return) are now “barred” from the building they paid for–unless they pay “another” fee to get in. Meanwhile, current students pay much less–and get in free! If you ever visit C’dale and are so inclined, go to the co-rec building (north of Grinnell and east of the Blue Barracks) and hang around the front entrance. You might see and hear alumni walk by, point to the building and comment “I paid for this building, but they won’t let me in unless I pay again!” What great continuing PR for the university with its alumni! By the way, the reason the Board and administration gave for barring former students was that they might “overtax the facilities.” The day after this was announced Gus Bode said: “Too bad the trustees care about overtaxing the facilities. They never worry about overtaxing the students.” Experiences like this jaded some students and discouraged them from working within the system to access funds earmarked for student needs.

Fortunately, some student fees went into funds that were more liberally administered. One of these was the so-called “Activity Fee.” The “Activity Fee” was collected from each student every quarter they registered and paid tuition. This fee was designed to be spent each year to fund a variety of student activities. Even in the ‘60s, there was at least $100,000 collected and spent each year under this fund.

Procedures varied over the years that governed application and use of these funds, but generally speaking, the lion’s share of this money was approved by the student senate based on applications from student organizations that had met certain requirements to achieve official status. Thus, in order to be eligible to even apply for funding, a group must be properly “organized.” This meant there must be a proof of “need,” for the organization (which could be a list of interested students, some kind of “constitution” or governing document, election and/or appointment of a governing body and officers, and official approval of these documents and processes). Usually, official approval meant student government as well as (university) administration approval.

This process was made to seem daunting for a reason. Although there was a pool of funds available, increased competition for the funds made life hard for those who had to decide. Also, once the funds were allocated, there were many regulations to follow in usage of the money. Allocation to a “fringe” group usually meant lots of headaches for the ensuing fiscal year. Finally, there was the issue of empowering a group that would be “troublemakers,” ie, give the administration a hard time. It was easier to squelch a potentially threatening group by making the initial organization/recognition stage difficult, rather than suddenly refusing to fund an ongoing group.

In 1967, there were SDS groups on campus. While it is unknown if any of these groups applied for official recognition, these groups represented one end of the spectrum the administration perceived as “criminal.” The inference can be drawn that any new group that might be perceived as similar to the SDS groups were not ushered to the red carpet fast-track.

Some readers may be older and have developed significant administrative skills, so establishing a new student group at a university may seem, from today’s perspective, rather simple. But try to picture an 18-19 year old, with the impatience of youth, little bureaucratic experience, buffeted with the pressures of 5-6 classes, dorm living, as well as the party and opposite sex distractions that only C’dale can offer, and one may be able to conceptualize the challenge of the stiff learning curve and need for unlimited perseverance and discipline required to accomplish major bureaucratic tasks. Add these challenges to the goal of creating a new organization whose purpose was to serve students exclusively, in a specific area where the administration had tried and failed (but would not admit failure). Finally, this was an area perceived by administrators as threatening to the control of communications as well as university protocol, procedures, and powers. These were the “general conditions” faced by those trying to create a student radio station at SIU.

Because of the perception of danger from so many interested groups, there seemed to be infinite hoops to jump through, and new ones were created every day. From the administration/faculty point of view, five years to complete (or not complete) a project was not too long (as illustrated by the overpass and Co-Rec debacles). But to students, being able to sustain an effort towards a goal for five and more years was not realistic. A number of efforts to realize ANY major project to primarily benefit students ended in failure or abandonment. Many never got off the ground. Some died for lack of follow-up. A small portion became obsolete. A few demised for lack of interest. Factionalism was fatal to others.

The key to success seemed to be first, an unwavering vision by a creator who could remain both spiritually inspirational and bureaucratically skillful. Second, the passion and energy of a member-nucleus able to focus on a common goal. Third, the leader’s ability to shepherd and marshall internal (members), and external (bureaucracy and others) elements towards that goal. Finally, a goal-oriented “can do” relentlessness, tempered by reasonable morals.

By 1967, the first element was already present.

Chapter 4

In the early 60′s, there was a main general decision-making body called the University Council. It contained representatives of faculty and others. There were sub-bodies of this, such as the Residence Halls Council, Student Council (Student Government), and Communications Council, which was essentially a committee whose purpose was to review campus and communications issues and make recommendations to the entire University Council.

After receiving the Lueck WCBQ carrier current station proposal in 1962, the Communications Council failed to act. In March 1963, President Morris issued a policy statement which charged the CC with the duty “to make recommendations to the University Council on all proposals for adding to or deleting from the University communications media.” Shortly thereafter, Richard Moore, then Student Body President-elect, requested the CC act on the Lueck proposal. In June, 1963, the CC did act. They recommended that the University Council approve it in principle, with the suggestion that “either the Residence Hall Council or Student Council submit a more specific proposal for review and approval” that would contain:

- Details of a student organization that would operate the station

- Programming goals and details about how the goals would be met

- A plan for University engineering assistance so FCC standards would be met

- A “Student Control Board” (with possible faculty participation) that would have authority to remove any individual from the station for cause

- Faculty “advice and counsel,” possibly from Broadcasting Service

- Control of advertising and revenue therefrom

In August, 1963, the University Council rejected this, sent the matter back to the CC, and told the CC to first get the proposal redrafted and then resubmit to the UC. In November, 1963, the CC instead decided that there should be an “Advisory Board for the Carbondale Campus Closed Circuit Radio Station,” comprised of:

- Three faculty advisors

- Student Body President

- Student Council President

- Residence Halls Council President

- Inter-Greek Council President

- Station Manager

and this board should prepare the revised proposal. This was only the CC’s recommendation; it could not proceed without UC approval.

In January, 1964, the UC rejected this. Instead, the UC instructed the CC to “investigate the alternatives for making the present FM programs (on WSIU-FM) available to the residence halls.” The UC felt that the student need could be addressed if students could just receive WSIU-FM. The idea of a student-run carrier current station was going backwards.

The CC then dutifully engaged Buren C. Robbins, Director, and Founder of the SIU Broadcasting Service, to prepare a report on the feasibility of making WSIU-FM available to all dorm residents, and how WSIU could address student needs. The CC also snuck in an additional item: Robbins should also evaluate how well a carrier current station would satisfy students’ needs.

Robbins’ report was issued in April, 1964. Its main purpose was a cost/benefit analysis of a university-funded installation of FM receivers in dorms so students could listen to WSIU-FM! The report enumerated these alternatives:

- Installing 1200 all-channel FM receivers (one in each then-existing dorm room) at a total cost of about $50,000

- Installation of the same receivers, but only in dorm lounges, at a total cost of about $12,000

- Installation of carrier-current AM transmitters in dorms to rebroadcast WSIU-FM, so WSIU would be made available to students on AM, at a total cost of about $7,000 plus $50/month for phone lines

- Same as 3, but the AM would have separate programming for an hour or so each day for “student announcements”

- Same as 4 but the AM could also be separated at any time for “announcements to students at any time”

- Same as 5 but separate the AM for more extensive original programs by and for students (but only with “strict control and supervision of the Broadcast Service”)

Robbins’ final conclusion was to recommend 4, based on cost and to “prevent the programs’ getting out of control were students to control all, or part, of that programming.” Robbins did say that if funds became available it might be OK to proceed with expanded student programming, but only “with great caution.”

After Robbins’ report became public, at least several students protested in letters. Students wanted the experience of managing and operating a radio station and making their own programming decisions. The members of the Communications Council seemed to understand this. While they reluctantly acknowledged that choice “d” was the best way for WSIU-FM to reach students, the CC members pointedly stated that this would not provide the experience students wanted. The CC then became defiant by insisting that their prior recommendations (to create an interim board and authorize a student station in principle) be reconsidered. Their April, 1964, report also said:

3. The Communications Council suggests that it might be in order for the University Council to recommend an overall review of WSIU-FM standards of programming in terms of both presentation and content.

The effort to create a student station was the victim of a “turf battle” between (on the one hand) administrators and faculty who wanted to facilitate student opportunities and (on the other hand) the broadcast service’s interest in controlling all campus media; as well other University Council members were concerned with “out of control” students making programming decisions. The CC did not seem to hold WSIU-FM in high favor. It appears that the University Council again refused to accept the CC recommendations.

By May, 1965, Fred Lueck, still at SIU, had found some help. Fred prepared a new proposal, but this time, he had lined up all the dorm presidents, Student Council, Student Body President, and all of them had endorsed the proposal. In fact, they had created a “Committee for Closed Circuit Radio,” of which Fred and Mike McDaniel were co-chairs.

This new proposal had these key features:

- Still no governing board

- Station would be funded by “amending the Broadcast Service’s budget”

- Had provisions for sales

- Some clumsy organization: Staff members appointed for one quarter only, Faculty Advisor appoints a “Manager,” and the advisor must approve all expenditures, appointments, etc.

- No engineering or programming details, not even how decisions would be made

This proposal was submitted to Dr. John Anderson, whose title was “Executive Director, Communications Media.” It appears that he was superior to the Director of the Broadcasting Service. He authorized a study on this matter by Ira McDaniel, Director of Broadcast Engineering at Oklahoma State University. McDaniel’s report was issued in August, 1965. His conclusion was remarkably astute and prophetic:

“The possibility of an open-air transmission system should be considered. Such a system would give full campus and off-campus coverage regardless of growth trends. The system would be central in nature and therefore require less material and manpower to operate it. The first costs would be lower for the open-air system. Problems with the FCC (about excessive radiation from carrier-current transmitters) would be all but eliminated. If an open-air station should happen to be commercial, the operators of the local station would be duly concerned, but that would be the case even with a current-carrier station. It should be decided which will be of the greatest concern…..the operator’s (university’s) interest, or the interests of the student body. The open-air system would seem to be the only sound system to merit consideration if a frequency is available and the author is sure there is.

“The author estimates that at the present rate in which FM channels are being filed upon in Oklahoma, there will be none left by 1969. The situation in Illinois is probably more acute. The possibility of a commercial FM for Carbondale, and both a commercial and non-commercial educational FM for Edwardsville should be considered. Once these frequencies are gone, it is probable that they will never again be available………… especially to educators.”

Sadly, this cogent and prescient analysis was obscured in an avalanche of discordant proposals, committee recommendations, and other reports. To his credit, Dr. Anderson tried to corral the issues by identifying many interested persons, rendering sets of copies of all relevant documents to them, and assembling them in an attempt to fashion some form of consensus. At this point, Dr. Anderson had assembled all the documents described so far. But there was a lot more.

In addition to their proposal to “amend the broadcasting service budget,” Lueck and McDaniel also submitted a document titled “Managerial Breakdown and Job Description of the Station Operating Policy of the Proposed Student Carrier-Current Radio Station.” A company called “H & R Broadcasting” submitted a proposal that they would operate the campus student station. John Kurtz and Buren C. Robbins presented a document entitled: “WINI–prepared for Carrier-Current.” There was a copy of a study from Michigan State University about their situation. There was a new (kind of half-baked) proposal for “Radio Thompson Point” that would feature, among other things, “announcements and music during meal times.”

Dr. Anderson was charged with the duty to render a report on this to Ralph Ruffner, Vice President for Student and Area Services. During a trip to Hawaii and Tokyo, Dr. Anderson wrote his report. While in Katmandu, Nepal, he wrote a letter “expressing his dismay” that the report had not been received yet. His report finally “turned up” in mid-November, 1966.

The long awaited conclusions were not surprises. The report stated:

- Students really wanted to manage, operate, and program their own station

- Buren C. Robbins really wanted the university to purchase equipment so that more students could listen to WSIU-FM

- The University Council really wanted any student programs to be controlled by the Broadcasting Service

- The students should have their own station, but not before the questions of who would own it (i.e. a non-university non-profit corporation) and how it would be funded were resolved (with no suggestion on how to resolve this – just that “legal counsel said it should be looked into”)

- That students, if motivated, should devise ways of funding the station

- No mention of an open-air station

No action recommended, except that Robbins’ idea (to make WSIU-FM available in dorms) should be funded, as it might “aid instruction,” and that WSIU do more to program to student needs. After five years of meetings, proposals, studies, reports, and analysis, the great organization and brainpower of the university responded to an obvious student need for a student radio station by suggesting further study, and spending money to obtain a student (possibly captive) audience for WSIU.

The WSIU-FM receivers-in-the-dorms idea never happened. It is unknown if there was any follow up by legal counsel to “look into” aspects of outside ownership and funding methods of a student station. Lueck and McDaniel eventually left SIU, possibly as graduates. There was some outraged reaction to Dr. Anderson’s report.

Some faculty stated the obvious—the university had failed the students. It had taken five years to accomplish nothing. The school was no closer to a student radio station and/or a radio service serving student needs than it had been in 1962, or, for that matter, 1862. Generations of students had arrived and departed C’dale and there was still no local radio for students, for service, for experience, for anything.

Supposedly structured for efficiency, the administration and bureaucracy had spun its wheels, passed the buck, ignored its own paid consultants, engendered territorial battles, and completely disregarded students’ needs. The administration and bureaucracy refused to prioritize students’ needs over administrative convenience. They ignored the efficiency of open-air broadcasting and procrastinated, stalled, and delayed. This is how they “served” their paying customers–the students.

When we assemble this story with what happened with the overpass, the riots of 1966, and the SWRF, a troubling pattern is confirmed. Far from isolated, this pattern of bureaucratic behavior to place student interests last continued. This is the landscape Jerry Chabrian “inherited” when he arrived as a freshman in September, 1967. He was not aware of all of this; and it’s probably a good thing. He might have been discouraged, but, knowing Jerry, he more likely would be mad, possibly mad enough to distract his focus.

Instead, Jerry merely saw a great need and proceeded to address it. The first thing he did was seek allies. He found George Bouros, a fellow resident of the “fourth floor zoo” in Wright II. Jerry perceived that, BEFORE decisions were made about a future station, he would ask for input. Those that participated would be likely to support the final plan even if all input did not appear in the final proposal. At least people would perceive that their opinions were considered.

Jerry’s plan was to seek as much student input as possible, as well as ask for administrative and faculty input and ASSISTANCE, but not PERMISSION, to proceed. This was smart because asking student opinion would activate students, create a hue and cry to proceed, and create a cutoff and defense against last-minute derailing counter proposals. Getting as many students on the bandwagon early also limited potential last-minute opposition. From the beginning, this was to be a STUDENT station.

The climate had changed at SIU, just in the three year period since the Robbins report had been issued. There was no longer a “Student Council;” now it was “Student Government” and “Student Senate.” There was even a grudging recognition that students at the college level were not the “children” they seemed to be in the early 60′s. Whether it was the draft, the war, increased political participation, the ’66 riots, or just the way the 18-20 year olds conducted themselves, there definitely was a difference. Jerry reports that there was an incredible vitality among SIU students at that time. “Everyone knew there were things to be done, so we just did them,” he said. The student population kept rising, the times were changing and there was an obvious gap between student needs and available resources.

One painfully obvious vacuum was in radio service. Jerry and George approached student senators. They found Senators Dale Boatright and Jerry Paluach willing to “pitch in” and help the cause. Dale and Jerry sponsored a bill introduced to the senate on January 17, 1968. This bill created a special committee to hold hearings on the creation of a student radio station, and a “Student Government Radio Division” to prepare a feasibility study and budget for the station. The bill passed, with the changes being that the Senate Internal Affairs Committee would conduct the hearings and Jerry Chabrian and George Bouros would prepare the proposed budget.

The hearing was held on February 15, 1968 from 2-4 pm at the University (now Student) Center. It was publicized in the Daily Egyptian. Administrators, faculty members, students, and others were personally invited to attend. Many did. About 40 attended the hearing, which was chaired by Sen. Paluach.

Jerry and George presented the “first draft” of their proposal, which included an equipment and construction budget. First up was the issue of the “build-out,” making soundproof rooms in the space the new station would occupy. Issues surfaced about whether union labor was required to erect the room partitions; if so, the build-out price could rise $20,000 or more, which would kill the project. This was a small issue within the greater agenda of the university. The unions were a major interest group in the expansion and administration of SIU. As a result of union support for SIU, the university became a union shop, unusual in Southern Illinois. As a union shop, part of the deal was that if certain work was done on campus and/or with certain university funds, the work had to be done by union personnel at union rates. Union contracts with SIU contained many requirements and exceptions, so there were lots of questions about this, which resurfaced later as a major hurdle. At this hearing, George offered that the head of Financial Assistance said student workers could be used at the student rate.

Dr. (then Mr.) John Kurtz attended, and asked some poignant questions. First he inquired about the transmitter costs and locations. He pointed out that Jerry’s estimates were low. Then they had this prophetic exchange:

There was a spirited discussion, led by Mr. Kurtz, about the station’s news and editorial policy. Jerry asked for suggestions. Mr. Kurtz pointed out that there should be an editorial policy that sets forth who had the final decision. Several in attendance felt strongly that the decisions must be 100% student.

George Bouros felt that the faculty and administration should have 50% of the control, because the station needed their cooperation to access university facilities. George stated a fear that he and Jerry kept in mind:

GEORGE BOUROS:

”I think anyone can come up with a radical idea, but if they don’t know how to take it tactfully to the University, I don’t see how you’re going to get your message across. Just by presentation, they (the Administration) will say good-bye.”

This led to a discussion on key points of station control. What positions will have what power? Will they be students? Who will select the persons for these positions? Should this be the Student Senate? Will they then control the station? These questions went unanswered, for a time.

After a discussion about programming, the meeting adjourned. This hearing showed the interest and sophistication of a diverse group that supported not only the concept of a 100% student station–but its practical success as well. Jerry and George made a trip to Champaign to check out WPGU in March. There was another hearing that month. George left SIU sometime in spring, and Jerry carried on. He revised the station proposal several times. Finally, it passed muster in the Senate Internal Affairs Committee– and was sent to the Senate Floor May 29, 1968.

The final draft of Jerry’s proposal employed this opening paragraph in the preface:

The early planning of a radio station involves consideration of the market to be served, site selected, station policies, personnel, the extent of programming, and, most important, the amount of capital available. This proposal takes into consideration all of the above ideas and forms them into a workable plan for the establishment of a Student oriented, student run AM radio station.

This is what appeared on the first page:

THE SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY STUDENT ORIENTED CAMPUS RADIO STATION PURPOSE: To provide Southern Illinois University students living in dormitories with a radio program service at present unavailable (sic) to them. To provide the student body and faculty a channel of communication for the discussion and review of student problems. To provide an activities outlet for the many students interested in broadcasting.

GOVERNANCE: The Southern Illinois University Campus Radio Station is to be governed by a Board of Directors, consisting of a Faculty Supervisor, two members of the Student Senate, the Station Manager, the Student Chief Engineer, and a representative of the SIU Broadcasting Service. This board is to be entrusted with the formulation of policies regarding all facets of the station’s operation.

Jerry had done his homework. He had reviewed all of the prior proposals and their treatments. In response, he had addressed many of the groups which had expressed objections or counter proposals in the past. The Broadcast Service would be represented. The faculty would be represented, by a “Faculty Supervisor” who would not only chair the board, vote on decisions, vote twice if there were ties, but also could refer board decisions to the Dean of Students, a member of the administration. The Student Senate would have two members, more than any other group. In theory, they would represent all students at large. Thus, Jerry had proposed a board of four students and two faculty/staff members, but he made it appear that there was still lots of faculty/staff control.

Another interesting section of the original final proposal in May, 1968, was the “Programming Policies.” The music was to be “…a moderate, yet upbeat sound, the ‘young sound.’” News promised “hourly reports with the headlines on the half-hour, and bulletins as the story breaks…to keep students abreast on both (campus and other) news fronts.” Public Affairs and Editorial policies emphasized “both views,” “equal time,” “seeking out great diversity of student and faculty opinion” and “balanced presentation of controversial subjects.”

The final paragraph of programming policies was entitled:

5. GOOD TASTE. It is the policy of the station to exclude from broadcast salacious and profane material, and material offensive to religious and socio- economic minorities. This policy does not apply to the expression of ideas; however it does apply to the use of language.

The proposal contained many pages of details of how carrier current transmission works, the buildings which would house transmitters, the station proposed budget, organization chart, equipment wiring diagrams, and related info. The proposal contemplated wiring Small Group Housing, Evergreen Terrace, and Southern Hills, which never happened, due to the need to have transmitters in every building. The proposal also took a position that advertising would be sold, and the main objectors to this would be the Daily Egyptian.

Jerry’s proposal passed the Student Senate May 29, 1968. Jerry had, in only one academic year, lined up more support and vaulted over more hurdles than all the others in seven years. But this was only the beginning. That night, Jerry was severely injured in a motorcycle accident. He was airlifted to a St. Louis hospital. His life was in danger.

Jerry’s injuries were severe. He endured a lengthy hospital stay. He was only 19. Yet he returned to SIU in the Fall of 1968 and persevered in his efforts to create a student radio station. In November, the effort’s senate supporters moved ahead to insure more student control in the future station.

Chapter 5

Meanwhile, other frustrated students unaware (or unimpressed) with Jerry’s efforts decided to start their own radio stations! With advancing technology came a store called “Allied” (a predecessor to Radio Shack). Allied sold “modules” that were low power AM and FM radio transmitters, powered by household batteries! Normally, these devices had limited usage because of low power output, low antenna, and only a few receivers within range.

In C’dale, low power broadcasting could reach thousands of listeners because conditions were unusual. First, enterprising students figured out how to increase the transmitting power of the modules. Also, in at least one case, the transmitter was on an upper floor of Schneider Tower, so there was a high antenna. Most important of all, there were a huge number of receivers within range. Schneider had 500 rooms and about 1000 residents. Just about each and every room had some kind of AM radio.

Starting in the late 60′s, various residents had attempted some form of pirate broadcasting. (The term originated from offshore transmitters in ships, situated beyond territorial limits of England). In C’dale, some pirate stations were not much more than a “play” radio setup, an extension of the turntable/microphone/amp/speaker that many of us fantasized with as kids. The pirate stations usually had erratic hours, undependable signals, and poor quality audio. Music selection was limited to the records that the “station owner” had on hand. One never knew if a particular station would be back on after breaks between quarters. While this was true grass roots radio, it could be argued that listeners were attracted mainly due to the complete lack of competition.

At first, the pirate stations might serve a few dorm rooms, or a floor. Gradually, this extended to a whole building, even groups of buildings. Thompson Point, a West Campus residence area, had at least one station serving most of the area. On the East Campus, there was WBHR, in Boomer, which served Boomer I, II, and III, along with adjacent areas in the East Campus. There were others, too, (such as WSEX, somewhere in Schneider, or was it somewhere on Wall Street?) about which little info is available.

WBHR started in early 1969. Jan T. Pasek had a homemade (tube), almost one watt FM transmitter. Ray Breddemann reports that Boomer residents were frustrated with KXOK’s lack of quality signal and programming. Jan, Ray, and a few others decided to pool their equipment, meet in the 3rd floor end lounge in Boomer II and put an antenna in the window.

The next fall, (69) WBHR secured some funding for equipment from the University Park Residence Hall Council. Ray reports that they filled a tire with cement and put it on the roof. They used 105.1. There was substantial staff turnover, and a political science major, Bill Bodine, took over. He decided the call letters should be changed to WISR. Future WIDB members Bill Tingley, Jeff Esposito, Jim Sheriffs, and Ray remained at WISR, which continued until the Spring of 70.

Ray reports that some radio pirates received threatening letters from the FCC around this time. This may have provided additional impetus for the pirate members to throw in with the new effort for a university wide student station. WBHR/WISR was only one of at least several pirates operating at the end of the 60′s in Carbondale.

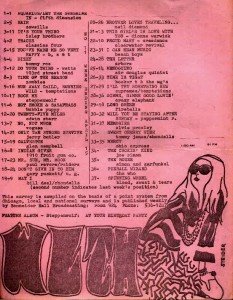

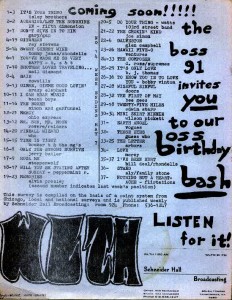

The largest and best-organized pirate was WLTH. It was located in Schneider, in a hair-drying room. The main leader of this station was Chuck White. Dan Mordini was a major member. Part of the WLTH nucleus were first and second-year students Howie Karlin, Tom Scheithe, and Jim Hoffman. Later, Dan Sheldon (and “His Voice”) came on the scene. WLTH operated from 7pm-1am weekdays, until 4 am weekends.

They were a top-40 format.

Tom Scheithe reports that, as a freshman Schneider resident, he encountered Chuck White at a dorm meeting. Chuck decided to start a pirate station in Schneider. He placed an ad in the Daily Egyptian. The initial meeting featured Chuck, Tom, Howie, Dan Mordini, Larry Rolewick, and Phil Phergilli, who worked at WLTH, Gary, In. This prompted the guys to take WLTH as their call letters; Phil gave them copies of WLTH ready-made jingles.

They secured the 9th floor “hair washing room” in Schneider. Everyone contributed equipment. Tom’s job was to regularly visit Dillinger’s Wire, Salt & Eggs (near the railroad tracks) to secure empty egg cartons. These were put up on the walls & ceilings of the hair drying room for soundproofing.